(A longer read)

Memories of Ilkeston past… your stories can add to this page.

Remember to tell it like it is (or like it was) and don’t be afraid to include any examples of our wonderful local dialect. Either send your contribution via e-mail to secretary@ilkestonhistory.org.uk or send by post to – IDLHS c/o 320 Heanor Road, Ilkeston DE7 8TH.

Albany Street

by Ken Richardson and Pat Smith (née Whitehead)

A side street off Nottingham Road, Albany Street was comprised of about eighty houses, with the great majority being terraced houses that had front doors opening onto the street. Each of these had small back gardens, an outside lavatory which usually had a tin bath hanging in it, a coal shed and a place for the dustbin. The tin bath was brought into the kitchen once a week, to be filled up from the copper in the corner, with bath night usually being Friday. There were also fourteen council houses and five detached houses, and these all had gardens at front and rear, and the luxury of an indoor toilet and bath. Halfway down the street were a greengrocers and a grocery/sweet shop, while at the top of the street was another grocers and a butchers/tripe shop.

The street itself was a huge playing field to us kids in the late 40s and early 50s, because there was very little traffic on it, and we played there virtually every evening after school. The lack of traffic was because, despite there being about eighty houses on it, there were only three folk with cars, and they drove them quite rarely because of the cost. There was also the occasional coal lorry, and we had milk delivered by Mr. Wheatley and his horse and cart, with the milk being measured straight from the milk churn into your jugs. The Co-op also delivered by horse and cart, and Mr. Laws(?) also had a horse and cart for his fruit and vegetable business. If the horse left a deposit on the street, it was a case of run for the dustpan and brush, so it could be put on the rhubarb plants up our small gardens. Hence the childish joke ‘We put horse muck on our rhubarb.’ ‘Oh, we have custard on ours.’

Although there was a green at the bottom of the street, we mostly played on the street because our parents could keep an eye on us, and we could easily be called in for tea, bedtime, or to listen to Dick Barton on the radio. The usual games were Storky, hide and seek, and Stick and Geezer, but the street was also the place for skipping, spinning tops, hopscotch, marbles in the gutter, skimming cigarette cards across the pavement up to the house walls, roller skating, biking and risking scraped shins from crashes when riding our trolleys down the street, which was on quite a hill. The trolleys were made out of spare pieces of wood, and sped downhill on four old pram wheels and, although we could steer them, I don’t remember any of them having any brakes apart from when we kids put our feet down. When autumn came, it was time for conkers, while the long, cold dark evenings of winter meant that we got out our winter-warmers, which were small open-top tins with holes knocked in them, filled with burning coals. These had wire loops at the top, which let us swing them around fanning the coals into flames. No health and safety in those days!

At weekends and during the school holidays, we had time to venture further from home, and this meant that in the summer we could go swimming in the top cut, because it was pretty safe being only about 3 feet deep. When we got better at swimming, we could go in the bottom cut, sometimes at Potter’s lock, but more usually at Sandy Bottoms near Sandiacre. We had to go there by bike along the canal bank from Hallam Fields, but it had the major attraction of being warm water, since it was down-stream from Stanton Ironworks, which had pumped hot water into the canal after some process or other. Apart from being warm, it was free, which gave it two major advantages over the old open-air Ilkeston Baths, which were opposite the police station at the top of the town.

During the summer holidays, we also went camping in Tormental field, which was near where we went swimming in the top cut, and we also camped in Shortwood, near Trowell, and went to a nearby farm for eggs and milk. We could go fishing at Mac’s claypit, which was about a quarter mile from Albany Street off Greenwood Avenue, which had the advantages that it was very cheap, we didn’t need any fishing licences, and the fish were easy to catch. We could also go canoeing or boating on Beauty Spot, which was at the bottom of Little Hallam Hill, just before the start of what is now Kirk Hallam. When we were feeling more adventurous and energetic, we would walk across the fields, past what is now Kirk Hallam, to get to Dale fishpond or the Hermit’s cave at Dale village, and we even camped near Dale Abbey one summer, as I remember.

In the summer we usually went on family holidays in a caravan near Skegness, but occasionally the destination would be a boarding house in Blackpool or Great Yarmouth, where all the top acts would be on at the theatres. Those kids whose dads worked down the mines, often went to the Miners’ Holiday Camp at Skegness or Rhyl.

Ilkeston in the late 40s and early 50s was very different from now, with four cinemas, trolley buses, two railway stations, plus one at Trowell, a huge ironworks, lots of coalmines, and several companies making clothes and stockings. All we Albany Street kids went to Kensington School until eleven years old, then it was off to Gladstone, Cavendish, Hallcroft or the Grammar, depending on whether we passed the eleven-plus or not. The large number of employment possibilities meant that anyone leaving school aged 15 or 16 could easily find work, and there were lots of apprenticeships available for those wanting to become mechanics, plumbers, electricians, builders, etc. The coal-mines and the ironworks took on a huge number of school-leavers each year, as did the many small clothing factories.

So, the Ilkeston that we remember was one that was a great place to grow up in, with lots of enjoyable things to do with your pals, and an easy place to get a job when we eventually left school.

Hallam Fields and Crompton Street

by Danny Corns

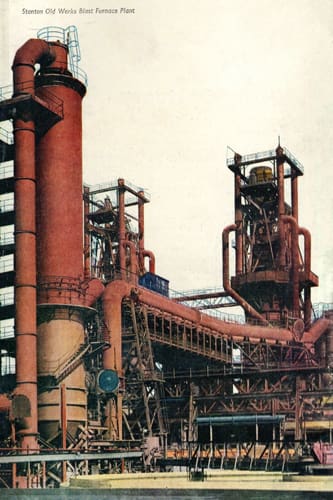

I was born in September in the shadows of the giant furnaces situated at the New Works of Stanton. This great iron making company employed around 9000 men and women at this works alone. Everyone who lived on Crompton Street was employed there. The houses belonged to the company and building them began in 1875, the company employing iron workers from the Black Country i.e. Tipton and Bilston etc who arrived via the Erewash Canal on boats run by Totty Bonser, a local boat owner and Fellows-Moreton & Clayton, carrying the families and their furniture. Eventually there were 148 houses, a pub/hotel, a grocery shop, a Post Office, a chip shop, a confectionary shop and the church, making the remote community self sufficient in every way. This was essential in the early days as there wasn’t any transport to and from Ilkeston, some three miles away, until the coming of the trams in 1903.

As a youngster growing up, my life revolved around the street. Kids playing football, cricket and games such as Storky, Bedlam, Stick and Geazer, Whip and tops (also known as Winder Breakers) – and making ourselves general nuisances. Every lad joined the Church Lads Brigade (CLB) or Cox’s Little Boggers as we were known. Reverend Machel Cox being the parson of St.Bartholomew’s and founder of the CLB in 1908. In the early days the girls joined the Band of Hope or the Girls’ Friendship Society.

My earliest memory is of falling under a trackless or trolley bus when I was about three. Good brakes those trolley busses had! I remember at the same age buying a bag of ‘tuffies’ (sweets) for a farthing (worth about one eighth of a modern penny) at Croot’s shop. This was also a chip shop until the war started in 1939. Mitchell’s was our grocery shop. I remember a giant book on the counter in to which the saving of a lsquo;tanner’ (six old pence or equal to two and a half pence today) was entered (we called it ‘packy’) to build up a fund for provisions. The new pub (The Stanton Hotel) was opposite our house on Frog Row, so called because of the giant frogs which lived in the cellars. Every Saturday night men would fight and even women at times. Next day they would all be drinking together again.

The war arrived in 1939 and I remember listening on the wireless (powered by an accumulator) which as kids we had to take over a mile away in a barrow to have charged up. Neville Chamberlain declared war and I remember a lone German Heinkell III dropping its bombs on Stanton on September 29th 1940. We spent a lot of nights in air raid shelters as Stanton was expected to be a major target because it made bombs and tank parts in the foundries I remember me dad shouting at the wireless when Lord Haw Haw came on. Stanton got a few mentions.

Our play ground as kids was the Iron Works itself. We would tease the ‘Tecs’ (Stanton security), dive under moving railway wagons! and go home when it was dark. Usually our mams would be shouting us in. We learnt to swim in the canal, in an area we called ‘ot watters’, due to the hot waste water pouring from the furnaces. We all had nick names of course. ‘Rubber Cutts’ – ‘Rustler Billings’ – I was nick named ‘Desperate Dan’ from the Dandy character.

The Church Lads Brigade featured strongly as kids. Every Monday night, some weekend parades and an annual camp at Ryle. We played football and cricket endlessly on the backs of houses using dustbin lids as wickets and anything we get hold of during the war. We had street fights with the nearby Kingston Avenue kids using catapults (‘gadies’) and dustbin lids on Sowjers Field. Stanton Sports Field was always available for cricket and football from about 11 years of age. We had a youth club, a boys institute for snooker, table tennis and darts. These are just a few memories from my very exciting younger days (to me at least).

Granby Farm

‘Barney’

Granby Farm was only of small acreage, running 10 cows, 2 heifers and a calf. Milking was by hand, the dairyman collecting the cans each morning using a horse and cart. Hard work, that’s for sure, and 6 days a week, but I haven’t a clue how much I was paid. We didn’t have a bull, of course. When a cow came on heat, a halter would be put on her and she’d be led along Cotmanhay Road to a farm which was somewhere near the trackless terminus. Often you’d see frightened mothers scurrying inside shop doorways with their infants when they saw us coming; worried I was leading a mad bull, probably.

The farm was owned by Herbert Beardsley. I called him Granpa, though he wasn’t a relative. He was around 76 years old, so badly affected by arthritis that he got about laboriously with the aid of crutches. Most of the time he was confined to the house. He blamed his condition on sitting for long hours on a horse-drawn cart in inclement weather.

Granma, his wife, suffered from what we now know as Alzheimers. I feel really ashamed, when I look back, at how we laughed behind her back when she’d come into the cowshed asking if I had seen her father (she herself was about 72 years old). Or she might ask where Herbert was, and I’d tell her he was in the house, whereupon she’d become impatient and say that no, the chap in the house was her father. Often she’d announce that she might go over to West Hallam to visit her mother, and that never failed to exasperate the old boy. ‘Visit yer muther?’ he’d yell at her, don’t be so daft woman, yer muther’s been dead these past 20 years, yer softer’n s**t you are.’

The farmer’s daughter was in her thirties. She’d been married, I think, but for some reason they’d parted. At least, her husband never visited, as far as I can recall. She ran the house, did the cooking, fed the chooks; a cheerful lass. Played the piano at the Cotmanhay Working Men’s Club every Saturday night. An enduring memory is of her playing ‘I dreamt I Dwell in Marble Halls’ on the piano in the lounge at home. It came back clear a a bell when I heard Enya sing it beautifully on one of her albums.

Nellie! Yes, that was her name. Helen, properly, but everyone called her Nellie. She organised the weekly hot bath for the family in the huge galvanised basin in front of the fireplace in the lounge (close to the piano!!); that was a Saturday ritual too. Mind you, being the age I was, and interested in girls, I often used to have a strip-down wash – cold water only – in the stannins after work was finished when there a likelihood of a ‘date’. Innocent days!!

She also made dandelion beer, to celebrate the end of hay-making. Sounds innocuous, but it has a punch for a lad who wasn’t used to that sort of beverage.

It was a time of great scarcity. Food was still rationed, of course, though we didn’t go without anything; we must have been the best-fed lot in all Derbyshire. From memory, we must have been allowed to kill one pig every six months for home consumption. Some chap came in to do the slaughtering, or maybe they took the animal away. All I ever did was to boil up tucker for it in a huge copper tub. The sides of bacon were hung from the ceiling in the dark cellar under the kitchen. Breakfast was always fried eggs and thick thick rashers. Aaahh, beautiful; I can taste ’em yet.

I hung around with several lads of my own age, though only one name comes to mind: Nanghi Riley. Gawd knows where the Nanghi bit comes from. He was a message boy cum rouseabout at a chemists shop ‘in town’ (Ilkeston). Sometimes, not very often, he got the chance to serve behind the counter. There was the time he pinched a packet of condoms (there were three to the pack in those days) from the shop. Three of us lads met three girls at the park on t’other side of Ilkeston on a Sunday afternoon. It was a place where lads and lasses congregated to exchange banter and get to know each other better. There was a lake in the park too. Anyway, Nanghi showed us all this packet of condoms, very daring see, then the packet was opened, and someone inflated one of them, like a balloon. Such laughter!! Hysterics ensued after one of the girls took her hat-pin and burst the thing.

Nanghi tucked the packet into his shirt and forgot all about it. Until next day, that is. Just as Sunday was church day, so Monday was wash day. And when Nanghi’s mum went to wash his shirt, what did she find but an opened packet of condoms, AND ONE WAS MISSING. That could only mean that her lad had done the unspeakable, right? Poor Nanghi. It took him weeks to convince his mother that he was still as pure as the day he was born.

However, though the farm may have gone, the memories remain as treasured items.

Hobson Drive

Stephen Flinders

Almost every spare moment of our free time after school in summer, or during the holidays were spent playing either down the Spinney Woods off the end of Derbyshire Drive, or in the Fields, an expanse of waste ground at the bottom of Hobson Drive bordered on one side by the railway embankment which carried the line into the Stanton Iron Works. The route across the fields also provided easy access from the top of Dale view via Allen Dale and on through towards Little Hallam. Having not revisited the area since leaving Hobson Drive some 30 or so years earlier, I was saddened to see our old stamping ground fenced off and converted to playing fields for the nearby school.

The Fields, as almost everyone knew them, was just about every local kid’s regular playground. When overgrown in spring and summer, it made the ideal site for endless war games and adventures, while in winter, a thick fall of snow (not that uncommon when we were children) would turn the place into a North or South Pole, where polar explorations would take place. Would the small gang of intrepid explorers reach the bottom of Allen Dale before their meagre supply of ‘tuffies’ run out?

I remember once when some of the older lads in the area built a large den at the base of this embankment. Constructed from discarded timbers, such as old railway sleepers, grass turves and other reclaimed materials. The den featured amongst its various mod-cons, a fireplace, fuelled by the scraps of coal which regularly fell from the passing railway wagons. Woe betide any younger ‘sprog’ who may have tried to gain entrance into this hideaway. I recall some of us once climbed on to the roof to seal the chimney up with a lump of grass turf, resulting in the inhabitants being flushed out coughing and choking. Great fun, until that is until they chased and caught us and gave us a ‘belting’.

A brook ran through the fields close to the embankment which we would regularly dam up to form a pool in which boats whittled from scraps of wood could be floated. As a child, you doesn’t notice just how dirty you can become within a very short space of time. I remember my younger brother and myself going down to play near the brook one day, still dressed in our better clothes. Returning home with them covered in mud resulted in another clout from dad. Likewise it was fun to slide down the embankment on our backsides, the coal dust providing an ideal surface. The wear and tear on our trouser bottoms must have been tremendous. Good job almost every mum in those days was adept with the sewing machine at making up clothes from old materials.

Anything could be adapted for use as a play thing. No computerised games consoles then. Armed with a dustbin lid and a broom handle, you or your friends took on the guise of an Ivanhoe or a Greek or Roman warrior. Or perhaps a Goliath, inspired after hearing the story at Sunday school. One of dad’s bean-poles strung with string could provide you with the means of almost taking out the eye of a playmate. A piece of wood for a sword or gun would suffice. Even better if you used dad’s tools to shape it into something more akin to the weapon it was meant to be, something which would often result in a squabble with a mate as to who should have a turn with it. Flags could be any old piece of cloth, coloured in with paint or crayon and pinned to a stick or pole. We caused some consternation once by copying a flag we had seen in a book or on television. Considering that it was only around 15 years since the war had ended, the sight of a gang of kids running round the street bearing a swastika flag resulted in its rapid confiscation.

Something I remember about playing at soldiers down the fields was the ease at which one could acquire an old steel helmet. The site must have been used after the Second World War for dumping old material. Helmets, webbing and even a mortar shell case were recovered from the site. Our discovery of the ammunition and the return of it to our house caused some panic. My step granddad buried it in the garden while dad contacted the police. Thankfully it turned out to be empty, though considering the tiny size of our garden; if it had been a live one, it would have probably taken the back of the house with it had it gone off.

We would never dream of venturing far from home. The furthest we would go would be as far as Lane’s shop and then down the jitty towards the Spinney Woods but never under the railway bridge and into Little Hallam. Likewise it was strictly taboo to go any further than to stand on the railway embankment. The other side was too dangerous. These were the slurry pits where Stanton dumped all sorts of waste materials. Occasionally a heavily loaded train approaching Stanton would skid on the rails and cause the grass on the embankment to ignite. Fire engines would be called and all would watch the spectacle. To think we would sit within feet of the trains passing by while the guardsman would throw a few sweets to us. But the thought of doing anything as stupid as putting debris on the line as some do today. We may occasionally put a penny on the track to see how flat it would become after a train had passed by. A little further along the line were the Oakwell sidings. It was rare for us to walk along the line to here as it was fairly busy with workmen and wagons etc and therefore a little too dangerous. Again, we seemed to know the limits to which we should go when playing out.

As with many families we probably had little money and life was relatively simple. A brass ‘threpney’ bit was your daily pocket money which was quickly spent at Lane’s shop on Lower Stanton Road. They sold everything a child would want. Sweets, comics, toys and far more besides. Their array of sweet jars along the shelves would cause you to keep them waiting while you made your choice until their patience ran out that is. Kay-lie (I can’t quite remember how it was spelt) was basically fruit flavour coloured sugar and left your finger multicoloured for ages after. ‘Jubblys’ – triangular lumps of frozen orange juice would seem to last an age, at least when you had managed to chew through their thick cardboard packaging. We would suck out all the juice before ’lobbing’ the remaining lumps of ice at each other or some unfortunate passer-by. Four-a-penny chews, sweet cigarettes, sherbet dips and gob stoppers were other favourites, though I must admit, as I looked up at the variety of sweet jars, I would wonder who on earth Dr White was, whose curiously bulky products were on the highest shelf in the shop! There was also a small green grocers next to Lane’s and a Co-op shop further along on the corner of Catherine Avenue and Stanton Road but again we would never dare to go that far without mum or dad.

If we chose not to have our pocket money day by day, we could save it until Friday when we would get two ’bob’ all in one go. With this we could purchase a Matchbox toy from Lane’s for one and nine pence and still have a few pence left for sweets or a comic, often containing some sort of cut out and make yourself novelty inside. The Topper, The Beezer and The Dandy were regular favourites, though my elder brother collected the Boys Own which contained stories featuring Dan Dare or tales from ancient history and features on how machines such as the hovercraft worked.

Look and Learn was another favourite though I can’t recall ever buying one. I think they used to cost a shilling and so were thought to be rather more expensive than our usual comics. Perhaps these were passed on from older children or from school. I remember there used to be a children’s magazine our Sunday School teacher would pass around which featured very colourful stories from the Bible. The stories came from both the Old and New Testaments and were filled with very exciting pictures. The Old Testament stories were my favourites. Noah and the Flood, the Fall of the Tower of Babel, David battling with Goliath, stories which we could re-enact down the fields, at home or even in our own imaginations. How many kids today would even know who these people from biblical antiquity were?

As mentioned above, our other play ground was the Spinney Woods which I am sure were probably quite small in reality but in our imaginations they became vast jungles where we played Japs and Americans or primeval forests, where monsters lurked. I believe these were cleared away in the late 1960s for housing. The remains of an ancient track-way once led through the woods, under the railway bridge and into Little Hallam.

Ilkeston Junction

Heather Flinders (née Walters)

I don’t remember moving to Willoughby Street but it must have been about 1959. We lived at number 10, a two up two down terraced house, one of five on our side of the street. At the back there was a big yard which we all shared. In the last house, next to us, lived the Edwards. They had a fence put up to keep their dog in (or was it to keep us out?).

Each house had an outside toilet and a boiler house for washing in and the tin bath hung on a hook outside the back door. The rooms were always damp and we wore liberty bodices (a thick vest) because we always had bronchitis.

I can’t remember all who lived their but in the first house lived a boy and girl named Peter and Lorraine Sisson. We used to play together but I think they were older than us. Further along in the next yard backing onto ours lived some cousins of ours who came to play in our yard. One day it was really nice and sunny and our aunt and uncle (you often called most close family friends, aunt and uncle then) who lived next door down the yard, had promised to take my sister Bronwyn and myself out for a picnic but on the day I went missing for several hours. My parents were worried sick not knowing where I was, a toddler having gone missing from the yard a year before and found drowned in the grounds of a nearby factory. People searching for me had no idea I was only in the next street with my cousins playing with some new friends in their yard. I had been put in my own dolls pram with the hood up so I had no idea where they had taken me but I thoroughly enjoyed myself until returning home and being banned from going out on the picnic with my sister.

There were several shops around the junction but we were only allowed to go there with our mum. One shop I remember sold broken biscuits from a tin that you could see inside and you would wish the lady would give you the fancy biscuits and not the plain ones. There was also a Post Office at the top on the main road, a lady named Miss Gethin lived next door. She would hold a Sunday School class at her house and we loved going there. It was about this time that my sister started school at Cossall, in the old school building situated on Coronation Road (now a restaurant). She was doing alright there until she came home one day rather upset because a teacher had made her wait for the toilet a little too long and after that there was no going back.

So mother tried to find another school to take her, myself included, as I was approaching my fourth birthday. Nowhere had room for us but Miss Gethin told us about Michael House, a private school on Heanor Road. She told us that many years ago, a Miss Edith Lewis had put money into providing towards an education for her father’s workers at his factory, which was just along Willoughby Street and that there was still money available to provide for children still living in the same housing. So we went for an interview and got accepted into this lovely school. Our mum was so proud and bought us both little uniforms (even though no other children wore one). We did look smart and never let our mother down. Several years later we left the Junction as the housing was damp and earmarked for demolition and also my brother was about to be born. We were given a house on Derbyshire Avenue at Trowell and several other families from the Junction were re-housed there around the same time.

Willoughby Street is no longer there, though its site can be traced amongst the numerous small businesses which operate in the area and the trains which once stopped at the junction station just the other side of the factories, have long since stopped running.

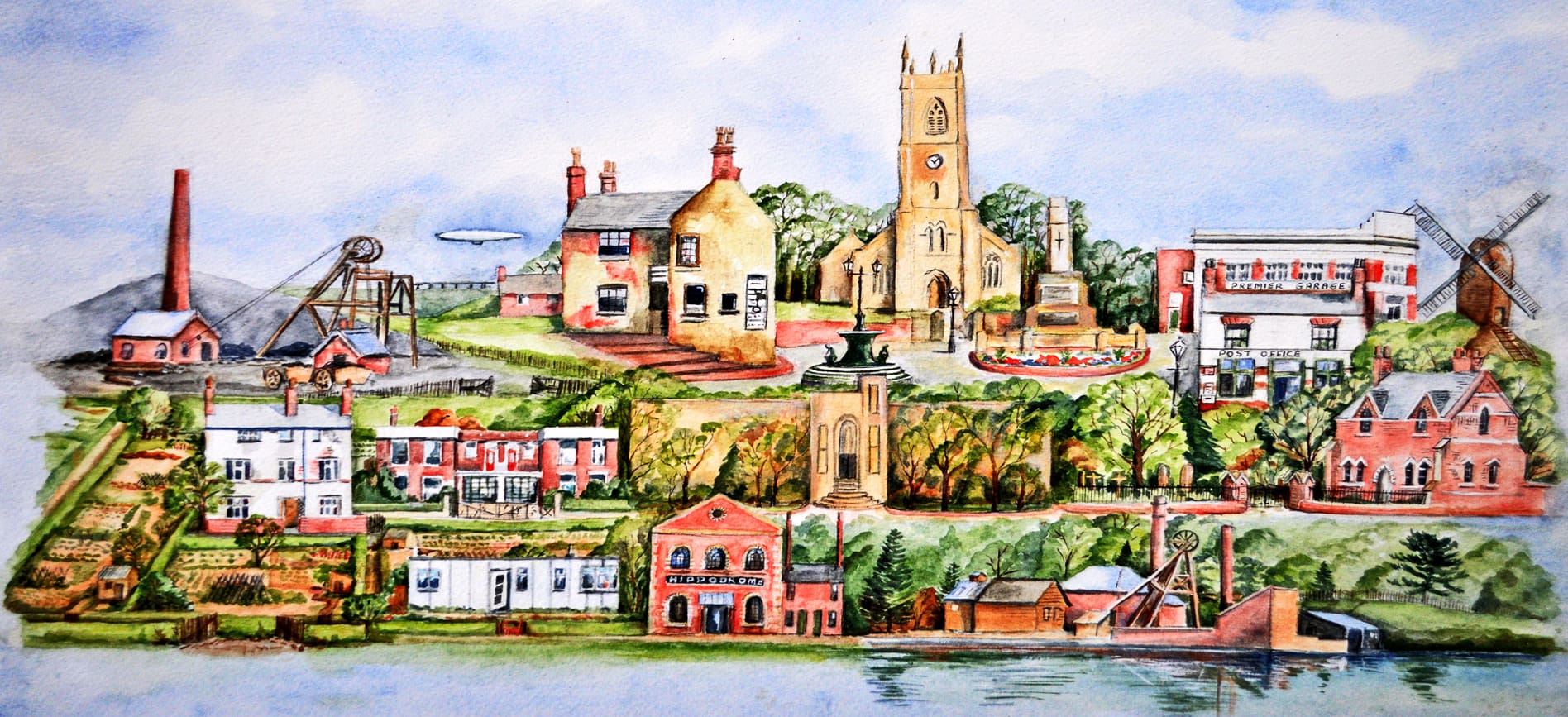

Original copyright artwork below by (c) Marion Axford